It feels like winter. Cold. Dark. In the train on the way to work, almost all my fellow passengers are engrossed in their phones, a few look out the window, nobody at each other. Across the aisle a man is obviously suffering from quite a cold, sneezing and coughing, while trying to avoid the suspicious looks from the other passengers. The floor is slushed and dirty, the heat is turned up, and people are sweating in their winter coats, but they stay on. Outside Fælleden rushes by like a blurry photograph in grey and brown hues.

Like most of the other passengers, I am absorbed. If I even notice my fellow traveller with the massive cold, it is only because I am in the middle of a story about a devastating pandemic, a strain of swine flu with a mortality rate above 99 % and an incubation period of a few hours that practically wipes out mankind. A sneeze from the man across the aisle and for a brief moment fiction and reality blend, and it strikes me how quickly a virus would spread considering how close to each other we live.

Most kinds of pandemic literature or movies make me think of Outbreak – the blockbuster of the 90’s starring Dustin Hoffman. It has occurred to me that when it came to movies (maybe not only movies), I was especially impressionable in my teens, which means that movies of the nineties have a tendency to emerge from my consciousness at any given moment – also uninvited. Outbreak follows the same narrative structure as the avalanche of disaster movies that appeared in the same decade: Catastrophe strikes on account of (aliens, Russians, a meteor, a virus, the sun, a volcano etc.), then comes chaos and finally people dying or surviving. What all these movies seem to convey is that when disaster strikes, instinct takes over. It is all about survival and human relations. Common to these disaster movies is also that when the aliens are vanquished or the meteor blown to smithereens mankind continues relentlessly, perhaps a tad wiser than before.

The representation of real disasters often follows the same structure, albeit with significant differences. In the days following the attacks on September 11, it was established in western media that reality outstrips the imagination. Writers of fiction were asked to comment on the events as if they were especially suited to navigate the incomprehensible.

In an article from September 15, 2001, British author Ian McEwan explains how a network station plays a voice mail from a woman trapped in one of the two burning towers. She made the call to her husband, who slept through it, and therefore never answered the phone:

“We heard her tell him through her sobbing that there was no escape for her. The building was on fire and there was no way down the stairs. She was calling to say goodbye. There was really only one thing for her to say, those three words that all the terrible art, the worst pop songs and movies, the most seductive lies, can somehow never cheapen. I love you.

She said it over and again before the line went dead. And that is what they were all saying down their phones, from the hijacked planes and the burning towers. There is only love, and then oblivion. Love was all they had to set against the hatred of their murderers.”

The image of the two towers, the blue sky and the plane. The image of downtown New York in flames, people escaping, covered in white dust. Images of firemen searching for survivors in the ruins. It was not merely the knowledge that the towers fell, but that you witnessed it happen. The media overflowed with personal stories in the immediate aftermath, almost as if it would dissolve the fact that the mediated realty, the hours spent in front of the TV with the same images dancing before your eyes, felt unreal, like it was one of the disaster movies of the previous decade.

But where the movies of the nineties all end with a classic redemption in the guise of a storm that passes or criminals in handcuffs, September 11 marked the beginning of a period where fear of the future dominates public debate. The immediate reaction sets the tone:

“I have never seen a generically familiar object so transformed by effect. That second plane looked eagerly alive, and galvanised with malice, and wholly alien. For those thousands in the south tower, the second plane meant the end of everything. For us, its glint was the worldflash of a coming future.

Our best destiny, as planetary cohabitants, is the development of what has been called “species consciousness” – something over and above nationalisms, blocs, religions, ethnicities. During this week of incredulous misery, I have been trying to apply such a consciousness, and such a sensibility. Thinking of the victims, the perpetrators, and the near future, I felt species grief, then species shame, then species fear.”

-Martin Amis

And in many ways September 11 is the beginning of an era, where rhetoric about terror, fear and religious fanaticism flows out of the western collective consciousness. And maybe in the middle of the sorrow, anger and despair, a space was created to imagine the unthinkable. In the junction between the personal story and the fear of the future a question arose. What happens after the end of everything? Where you do not just try to make sense of the catastrophe, but of life beyond it. Enter – or maybe – re-enter the post-apocalyptic narrative.

I suppose it would be disingenuous to link significant world events to a genre, especially since post- apocalyptic stories saw the light of day before September 11. I also doubt that you can make a direct connection between September 11 and refugees being housed in tents while it snows, or the Danish government warning more to come by advertising in newspapers and issuing poorly concealed threats about the removal of wedding rings. But this is the kind of thing that feeds the imagination with thoughts of a post-apocalyptic society.

Most post-apocalyptic stories after 9/11, like Cormac McCarthy’s novel “The Road”, puts forth a horrid scenario, the world as a waste land occupied only by thugs and cannibals. A father and his son, and their hopeless quest towards the sea, it is not even a story of survival but of love and death. Or the TV-series, “Walking dead”, where a virus transforms people to zombies, and a tough gang of adrenalin ridden individuals are in a constant battle for survival. The action seems to be reduced to oversimplified dilemmas like: if I shoot the zombie to my right, the love of my life will die, and if I shoot the zombie to my left, everybody else will. Though very different in outlook (and quality), what they have in common is that it does not look good for humanity post apocalypse. And not merely because mankind has shrunk significantly in size, but because the individual influenced by apocalyptic circumstance is depraved.

This brings me back to the train ride. One of the reasons I am totally caught up on my way to work is that in Emely St. John Mandel’s novel “Station eleven” there is room for both depravation and beauty.

The novel takes place before, during and about 20 years after the outbreak. The first few years are described as bloody and dark, and 20 years later, it is still not safe to travel. The novel follows a theatre company touring through small populated villages somewhere in North America. Even though the novel is structured around a recognisable plot, a prophet as the antagonist, who makes the story progress, the author confronts the notion that fear is the dominant element in a post-apocalyptic world. What drives the novel and the travel company forward is the insistence that survival is insufficient, that as human beings we will always be drawn by curiosity and towards beauty.

”The symphony performed music – classical, jazz, orchestral arrangements of pre-collapse pop songs—and Shakespeare. They’d performed more modern plays sometimes in the first few years, but what was startling, what no one would have anticipated, was that audiences seemed to prefer Shakespeare to their other theatrical offerings. People want what was best of the old world, Dieter said.”

The insistence on touring through the dangerous landscape is in itself a manifestation of the human will to live. As classic explorers they are in constant movement from town to town, and the ever present threat of prophets, ferals and bandits are balanced by an indomitable curiosity. To underline this, the company moves through settlements that have established libraries, archives or even newspapers, and an airport houses “The museum of civilization”, where driver’s licences, stilettos and iphones are on display. It may be post-civilization, but it is ingrained in human nature to venture beyond mere survival.

However, survival is a central theme in the novel, but underplayed and all the time balanced by a counter narrative which takes its point of departure in human beings acting, well… human. The novel is ripe with characters, who do not just survive, but reflect upon the altered reality. From conversations about how much your children ought to be taught about the old world to the acknowledgement that you have drunk your final capucino and listened to the sound of an electric guitar for the last time.

”I spent a lot of time thinking about civilization. What it means and what I value in it. I remember thinking that I never wanted to see a war zone again. I still don’t. There’s still a world out there, Jeevan said, outside this apartment. I think there’s just survival out there, Jeevan. I think you should go out and try to survive.”

Jeevan is one of the characters, who survives the deadly virus in “Station eleven”. Like all other characters in the novel Jeevan life is connected to the actor Arthur Leander, who dies of a heart attack prior to the outbreak. Jeevan works for several years as a paparazzi and tabloid journalist with Arthur Leander as his favourite victim, but is never happy with his job. His life is characterised by bitterness and a hazy search for purpose through an honourable profession. He survives the virus and contrary to his brother’s premonition, Jeevan has, 20 years after outbreak, found his purpose, and is practically happy:

”Even after all these years there were moments when he was overcome by his good fortune at having found this place, this tranquility, this woman, at having lived to see a time worth living in.”

Contrary to the time before the disaster, Jeevan is no longer searching for a purpose. He is the functioning doctor of a small community, and has found a woman he loves. Few of the other characters experience quite as clear cut a transition as Jeevan, and to the travellers in the theatre company, who insist that survival is insufficient, restlessness and art are the motivating factors.

One of the actors, Kirsten, carries two volumes of a graphic novel, Station Eleven, drawn by Arthur Leander’s first wife, Miranda. The novels are Miranda’s life’s work and 20 years later, Kirsten’s most precious belonging. Their creation, sources of inspiration, colours and stories are described in such detail that the comics by and by feel as real as the novel itself. Miranda is never more animated and alive than when she is absorbed in her work, which becomes an anchor and the permanent fixture around which her life revolves: I could throw away almost everything, she thinks, and begin all over again. Station Eleven will be my constant”. Almost as if to underline the importance of art, Miranda’s graphic novels are never published, yet 20 years after the outbreak they carry enormous importance to both Kirsten and the prophet, and therefore also to the progression of the novel. To the reader the comics are hidden just below the surface of the novel, like a work within the work, and however much you would wish to actually see them, it is impossible. That the graphic novels carry the same title as the actual novel only seems to enhance the impression that the imprint of art is intangible, but nevertheless of great significance.

It is tempting to conclude that the author is championing the idea of culture as the glue that binds people together. But she focuses on culture in the widest possible interpretation of the word, and as an extension of the human will to live. She does not thereby indicate that the world is a better place post apocalypse, but that men or women have the exact same potential for good or evil, ugly and beautiful as now. The dark post-apocalyptic stories are balanced by the impression of the individual as nuanced, and this in turn creates a space in which to ponder how to build society from scratch, when you know what you have lost.

We stop at Copenhagen Central Station. Most people get off, but I am continuing to Nørreport. Everybody is lining up to get out. The man with the cold gets up, is sort of stuck, wet eyes and rednosed. Suddenly the line divides, a woman waits, so he can get out. They look each other in the eyes, a thank you and you are welcome is exchanged. Spring is coming.

“What was lost in the collapse: almost everything, almost everyone, but there is still such beauty. Twilight in the altered world, a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in a parking lot in the mysteriously named town of St. Deborah by the Water, Lake Michigan shining a half mile away. Kirsten dressed as Titania, a crown of flowers on her close-cropped hair, the jagged scar on her cheekbone half erased by candlelight.”

-o0o-

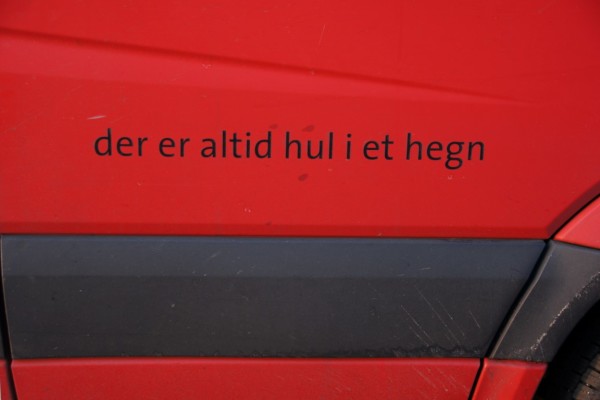

Like so many times before my sister has helped me with the photographs. I was not particularly proud of my description of the photos I needed for the post, which sounded something like ”desolate but beautiful, raw but beautiful, dark but beautiful etc.”, but she has once again managed to create the exact atmosphere I was trying to convey. Thank you! The pictures are from one of her favourite walks at the moment to Refshaleøen, which is a derelict but upcoming environment, with both hipsters and junkies abound. A thank you also to my reading buddy Mikkel Christoffersen for pointing me in the direction of this pearl of a novel.

Should you feel like reading more features from the days just after September 11, you will find some of them here. And if you find Emely St. John Mandel interesting, you can find more info on her work here.