To mark the 150th anniversary of the first publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, I felt like I might want to write a bit about the adventure in an un-academic way, though it is hard and oddly liberating at the same time. I felt I might want to because I have, since becoming a student, started to think about language and nonsense in a very different way. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a story, which is filled with nonsense and crazy talk, but the kind that asks you to pay attention to the way you think and the way you think is often in language.

A funny thing about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, other than it being funny, is that it is a book categorized as a children’s book. Genre serves to indicate what to expect, it groups things in kinds and likeness. So, like a reader knows when reading a comedy that all will be well at the end, we know what to expect from a children’s book. But what does one expect from a children’s book? Perhaps a book with a clear and simple plot. Alice’s Adventures doesn’t really have a straight forward plot structure, unless you count a girl falling down a rabbit hole, eating various items to change her actual physical size, talking to a caterpillar, going to a perpetual tea party with other talking animals and so on straightforward. Perhaps this plot is not completely implausible for a children’s story, after all one of the most famous children’s stories is one about two siblings murdering a witch by pushing her into an oven. However, what I think makes Alice’s Adventures extraordinary is the second checklist question. Does it have simple understandable language? No, not at all, it is quite nonsensical, some people insist. I might draw out the example of the hatter’s song, which was sung at the red Queen’s concert, to her great displeasure, and later for Alice. The Hatter’s song goes like this;

‘Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!/ How I wonder what you’re at!/ Up above the world you fly/ Like a tea-tray in the sky./ Twinkle, twinkle’ –(Alice, end of chapter 7)

You might recognise the song as a variation of Twinkle, Twinkle, little Star, but changed in the same way a child might change the lyrics when not able to remember them or just to make it more fun. But the parody perhaps reaches beyond the convention of its creation into our associations and memories with that song. Humorously, any tender, sentimental moment between parent and sleepy child is punctured by laughter, and the song is made present and malleable by merriment, a treatment given to many things in Alice Adventure.

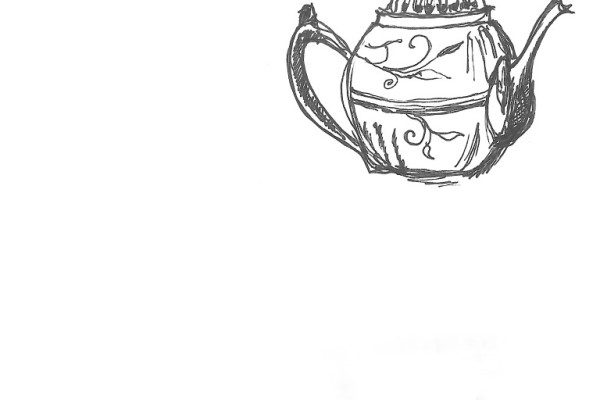

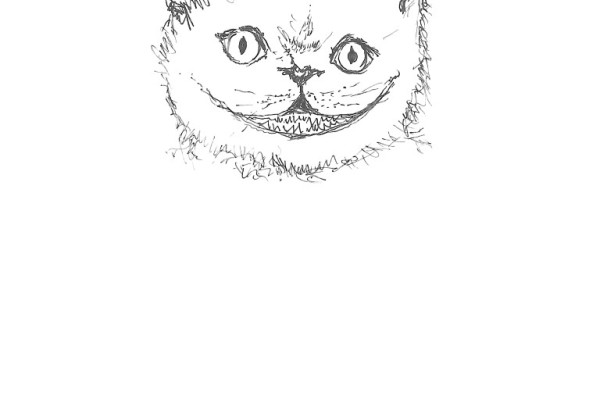

Illustration by Fiske. Chapter 7 – A mad tea-party. (Alice does not mean to meet the hatter, she goes to visit the March Hare on directions of the Cheshire Cat, little does she know that he is at the tea-party). “’Your hair wants cutting,’ said the Hatter. He had been looking at Alice for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech.”

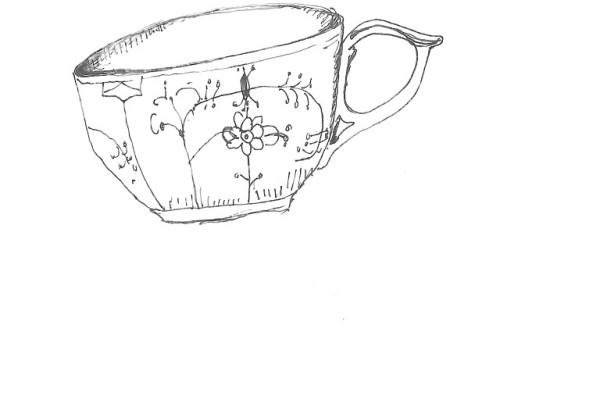

Illustration by Fiske. Chapter 4 – The rabbit sends in a little bill. (At exactly three inches the caterpillar is an imposing figure perched atop a magic mushroom. Alice Asks him for advice regarding her constantly changing size). “She stretched herself up on tip toe, peeped over the edge of the mushroom, and her eyes immediately met those of a large blue caterpillar, that was sitting on the top, with its arms folded, quietly smoking a hookah, and taking not the smallest notice of her or of anything else.”

I would like to say that children do not make up what kind of book, a book needs to be, to be a children’s book, but Lewis Carrol or Charles Dodgeson, captures the way a child might think and speak in Alice’s Adventures quite wonderfully, and as such it fits quite well. He captures the disordered connections between idioms and sayings that aren’t fully mastered, the propensity to play, the need to experiment and to reorganise language as a way of owning it, the bewilderment that a child feels at strange grown up conventions. And their attempts to fit in and not be so strange and in Alice’s case to impose some kind of logic on what seems like madness. All of these play out in similes of recognisable adult scenes, the tea party, for instance. Such a gathering might seem strange to a child, all that sitting around, talking and moving only occasionally and then just to talk to someone else, and how the party seems to go on forever. In a strange dreamlike way, we see the things that might seem absurd to an outsider highlighted in the Mad Hatter’s tea-party.

‘“I want a clean cup,” interrupted the Hatter: ‘let’s all move one place on.’ He moved on as he spoke and the Dormouse followed him: the March Hare moved into the Dormouse’s place, and Alice rather unwillingly took the place of the March Hare. The Hatter was the only one who got any advantage from the change; and Alice was a good deal worse off than before, as the March Hare had just upset the milk-jug into his plate. (Alice, end of chapter 7)

Perhaps, one could interpret this an absurdist view of tea-party mingling, or an attempt to solve the problem of wanting a clean cup, but not wanting to clean it, only to discover, through quite empirical means, how short such a solution as moving one down falls when met with a distressed milk-jug, poor thing.

I must not be too dismissive of genres, however. I tend to find them limiting and a little obscuring, but genres are useful, as they denote kinds and as people, we mostly think in kinds or likes, metaphor and metonymy. However, sometimes genres get in their own way, as people, well me, tend to think that the genre a book belongs to is an absolute expression of its pages, or an attempt to absolutely express what a book is. Therefore, while genre for some, well me again, seem to limit a book’s aspects, it is a useful method of categorisation. Luckily, it does not limit who can read what books; otherwise, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland would probably not have as many readers, since the serious adult would not find much of interest in a simple book for children, or so they might think. In any event, I speak from experience, I was one such person who when prompted to read and analyse a bit of the book, by a university professor, for class, thought it a bit odd and tedious, I wanted to get serious, (what an utterly useless thing to want to do!) However, as I got started I was quite captivated, and as a result, I have learned that expectations and predispositions are as dangerous as they are necessary and unavoidable, perhaps even useful at times, a learning I now share quite obnoxiously with you.

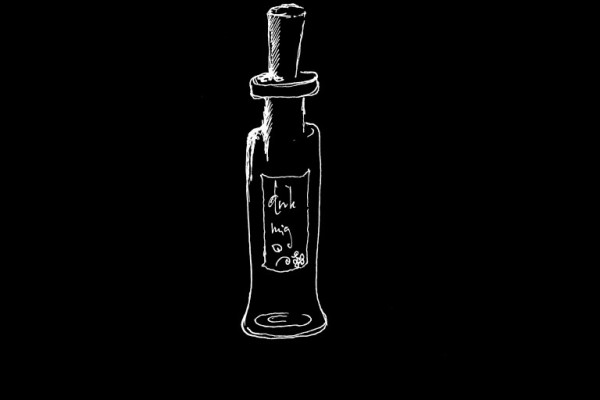

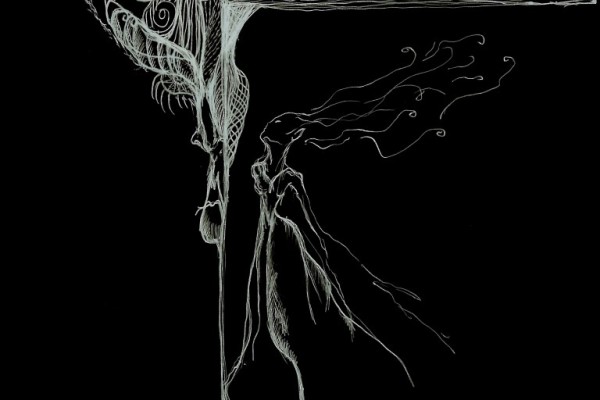

Illustration by Fiske. Chapter 7 – A mad tea-party. (The host of the mad tea-party, he lives in his house, which quite thematically has hare ears for chimneys). “The March Hare took the watch and looked at it gloomily: then he dipped it into his tea cup, and looked at it again: but he could think of nothing better to say than his first remark, ’it was the best butter you know.’”

But I seem to have gotten a bit off track, if a track there was or be. I believe I was gushing over the language of the book, and you might say if you are clever that I am being a tad bit unfocused, but I would ignore you and fall head first into my giant teacup. The language is fascinating because it plays with metaphor and metonymy, that is, one’s expectations of language. To clarify, metaphor works on the basis of substitution, while metonymy works on the basis of connection. In a confusion that is reminiscent of lifting a milk carton that is expected to be full and finding it empty, so that the hand grasping it flies skyward in a ridiculous gesture of ’hail the dairy,’ the mind is jarred and surprised, it must reorder its expectations to understand what just happened. Such a place is Wonderland, a place of constant reordering and well, wonder, in the what?sense of the word, not the wow!sense. An example might be found in Alice’s encounter with the Cheshire Cat; ‘“Well! I’ve often seen a cat without a grin,” thought Alice; “but a grin without a cat! It’s the most curious thing I ever saw in my life.”’(Alice, end of chapter 6) The cat, in an effort not to frighten poor Alice, disappears not slowly, but gradually, starting with the tail and ending with its predatory grin, which lingers for a bit without its cat. Which begs the question, in theme with the book, which asks many questions but answers few, is the cat vanished somewhere else without its smile? And if it is without its smile is it then just a cat? Or when it disappears is it just invisible? But then it’s still there, right? Because, being gone or vanished implies being somewhere else, does it not? Because, if you are, you cannot just not be, and to be you must be somewhere, must you not? And doing it gradually, are you then not just leaving?

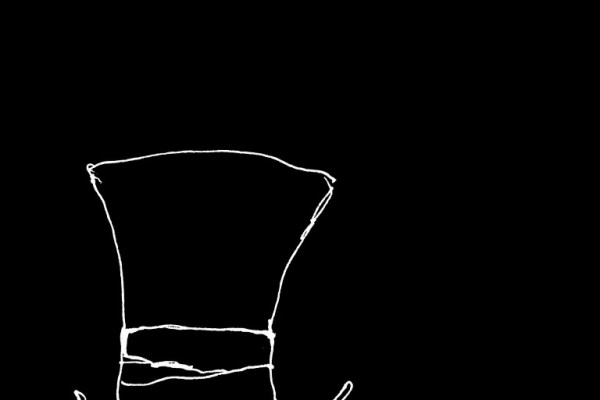

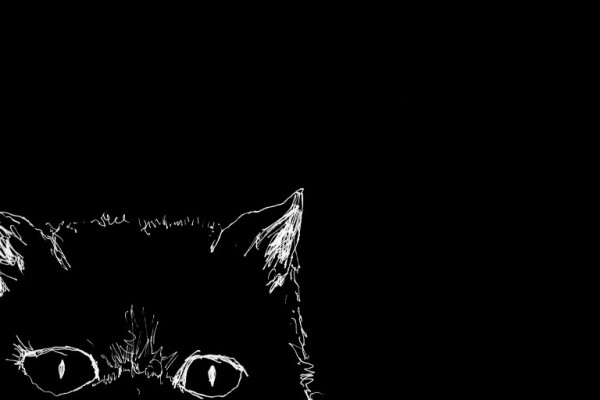

Illustrations by Fiske. Chapter 6 – Pig and pepper. (Helpful not just with directions, but also giving Alice an insight into the nature of the good people of Wonderland, (they are all mad even herself), the cat first appears in a tree). “The Cat only grinned when it saw Alice. It looked good-natured, she thought; still it had very long claws and a great many teeth, so she felt that it ought to be treated with respect.”

Alice’s adventures in some ways shares a child’s confusion and delight of new discoveries with the reader. To a child or a person who has not heard the saying, children should be seen not heard, it might not seem logical. As such, when the Mad Hatter says to Alice after she says she has to beat time to play music, ‘He won’t stand beating. Now, if you only kept on good terms with him.’(Alice, end of chapter 7) It might not be such an illogical reply. You see, one beats time to set a rhythm and to keep pace when playing music, but in a clever turn, poor time is sorely abused and later murdered by the Hatter’s twinkle song, which he sings at the Red Queen’s concert. A melodic murder that dooms the Hatter and friends to perpetual tea-partying. The difference is the ‘actual’ meaning and the ‘figurative’ one. Like a child, because they lack experience, the people of Wonderland cannot seem to tell the difference, in fact, there does not seem to be one. So, the metaphor beating time is understood as an actual act and not the figurative expression and we are then asked to re-examine our preconceptions about language.

We cannot passively receive in Wonderland, we must actively engage, in a sense we must play, wonder, and learn, just like a child that meets a new thing, just like Alice. The book has a language that asks us to follow it to the root of its beginning, to get lost in the many branchings and in that lostness it shows us the possibilities of language, and how it might be a game to urge the root to grow even deeper. Granted Wonderland is a scary place, with its smiles and head chopping queens, at times uncannily so, but humour punctures fear adding another perspective. As a reader or analyser, it is easy to lose perspective with questions like; what is the message? What is it meant to do as a story? Maybe it is not really meant to do anything other than entertain you for a while, so that you might lose yourself in other thoughts, maybe it should just tickle your imagination and leave you with a little smile, as long as you do not leave that smile. As such, we go to a strange place to learn we are always strangers and that we are all mad here, and what fun!

-o0o-

And what fun it is to have guests! We are privileged to welcome two of our favorite people as regular guests on kooiink.com. A monstrously huge thank you to Robyn Kooistra for sharing her thoughts on the nonsense of Alice and her adventures, and to Fiske for bringing them to life in her exceptional illustrations. A more devious march hare and self-important caterpillar have yet to see the light of day. And also a big thank you to Erling for helping us turn white into black.

Learn more about our esteemed guests